One of the biggest misconceptions that I see about hyperlexia is that hyperlexia simply means early reading so, therefore, all early readers are hyperlexic. But that's actually not the case.

There are early readers who are hyperlexic.

And then there are early readers who are not hyperlexic.

As I like to repeat a lot around here and on Instagram, there is so much more to hyperlexia than just the early ability to read. There are other traits that have to be in place in order for it to be considered hyperlexia.

In other words, there are key features and differences that separate hyperlexic readers from other precocious (i.e., non-hyperlexic) readers. Those differences are what we will take a look at below.

Precocious Reader or Hyperlexic? 10 Key Differences

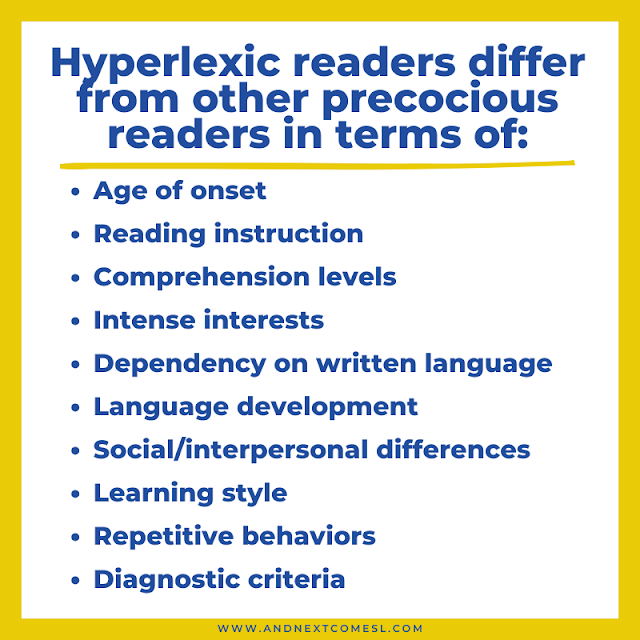

As you'll soon see, there are 10 ways in which hyperlexic readers differ from other early precocious (i.e., non-hyperlexic) readers. They differ in terms of:

- Age of onset

- Reading instruction

- Comprehension levels

- Intense interests

- Dependency on written language

- Language development

- Social/interpersonal differences

- Learning style

- Repetitive behaviors

- Diagnostic criteria

We're going to take a closer look at each of these differences and examine what the research has to say about these points.

The Differences Between Hyperlexia & Other Early Readers

It can be helpful to think of hyperlexia as a specific type of early precocious reading ability. So, keep that in mind as we go through these key differences.

1. Age of onset

The age of onset for hyperlexia is "consistently before the age of five years...and often much younger, starting at 18 months, which is, to our knowledge, about 18 months earlier than the earlier reported precocious reading case in typical children." (Ostrolenk et al., 2017). For example, my hyperlexic son started to read before his second birthday. That's pretty darn early!

It is worth noting, though, that the age of "onset is a frequently mentioned feature of most cases of hyperlexia but it is not diagnostic in itself." (Hopper, 2003).

However, the age of onset can help us separate hyperlexic readers from other precocious readers. After all, the early reading ability occurs much sooner and with more intensity in hyperlexia. In fact, research has shown that hyperlexic readers begin reading at least one year before most precocious readers (see: Healy, 1982) or, as the quote earlier in this section noted, 18 months earlier than precocious reading in typical children.

2. Reading instruction

With hyperlexic readers, it's important to remember that they learn to read with no formal instruction. In other words, their ability to decode is self-taught and "none taught the child how to read." (Healy et al. 1982).

Other early non-hyperlexic readers may also be self-taught so how can we separate hyperlexic from other early readers in this case? Well, it often helps to look at their language abilities (something we'll touch on more in the language development section).

As Ostrolenk et al. (2017) points out, "The main differences between typical and hyperlexic reading acquisition are that (1) the former relies on previously acquired language abilities, whereas the latter frequently emerges before any communicative oral language appears." In other words, the reading ability in hyperlexia often appears before the child has even learned to talk, whereas other early readers rely on their language abilities when learning to read.

Finally, there are some early readers who have been explicitly taught how to read. These early readers cannot be considered hyperlexic for this reason.

3. Comprehension levels

One of the biggest differences between hyperlexic readers and other early readers comes down to comprehension. For hyperlexic readers, they have "advanced reading skills, relative to comprehension skills" (Ostrolenk et al., 2017), whereas other precocious readers have strong or even advanced comprehension skills.

Keep in mind that "hyperlexia is viewed as a type of precocious reading, so that precocious reading refers to precocious reading without (i.e., hyperlexic) and with comprehension (i.e., non-hyperlexic)." (Grigorenko et al., 2003)

That means, if comprehension and decoding levels are similar, then that reader is likely just a precocious reader and not a hyperlexic one. But, if there's a discrepancy, it's hyperlexia.

Remember, a "unifying characteristic of hyperlexia is that all children are precocious and self-taught readers who have a fascination with letters and reading but have poor comprehension of the written word." (Miller, 1999 as quoted in Murdick et al., 2004) Or, as Shari B. Robertson (2019) put it, "for those with hyperlexia, there is a substantial gap between word-level decoding and overall comprehension of text."

So this comprehension piece is one of the best ways to differentiate hyperlexic readers from other precocious readers.

4. Intense interests

I mentioned earlier that hyperlexic reading starts sooner and with more intensity. Part of the reason why it's more intense has to do with the passion and fascination that hyperlexic readers have for letters and written words. Actually, "researchers acknowledge the presence of this 'passion for printed word' as one of the key features of hyperlexia." (Grigorenko et al., 2003)

Just to give you a better idea of this intensity, "families spoke of obsessive interests in letter and number blocks...and reading every bit of print the children see in their environment." (Newman et al., 2007) Yes, literally everything.

As Hopper (2003) noted, "the preoccupation with print often replaces other types of childhood activities" and one mother estimated that her hyperlexic children's interest in playing with letters "occupied 90% of both children's free time." (Ostrolenk et al., 2023) Which honestly, sounds pretty darn accurate based on our experience.

Grigorenko et al. (2003) also highlighted that the "presence of both obsessive preoccupation with and pleasure from written stimuli, experienced by children with hyperlexia not only at the emergence of their reading skills, but throughout their lives, often overshadowing and even forcing out developmentally appropriate activities." In other words, their interests are all encompassing and last for years.

One final quote that I'd like to share suggests that "hyperlexia manifests itself as an intense, transiently quasi-exclusive interest for all types of printed material, plausibly without an equivalent in non-autistic children at this age." (Ostrolenk et al., 2017). This point is one of the three main differences between typical and hyperlexic reading acquisition that the authors highlighted. The other two differences were the age of onset and their language abilities.

So, unlike hyperlexic readers, other early readers often have interests in broader subjects or topics and their interest in these topics aren't as deep or as intense. Nor do these interests necessarily dominate their childhood for years.

5. Dependency on written language

Hyperlexic readers depend on written language and visual instruction in order to learn and acquire language, whereas other precocious readers do not.

As the Canadian Hyperlexia Association (now defunct) mentions in their What is Hyperlexia? PDF, "If it isn't written, it may not exist." That's why we have the motto of "When in doubt, write it out!" for hyperlexic kids. They need the written word. Plain and simple.

6. Language development

There are also differences in terms of language development between hyperlexic readers and other early readers. For instance, hyperlexic readers have "significant difficulty in understanding and developing oral language" (What is Hyperlexia? PDF) and learn language via gestalt processing.

As a result, hyperlexic learners often have language delays and rely on a lot of echolalia to communicate. In fact, "receptive and/or expressive language delay was a very frequent finding" in hyperlexia research (Hopper, 2003).

Also, it's worth noting that the hyperlexic child's reading ability usually appears before they've even learned to talk. Take the mother in Healy's 1982 paper who "felt alarmed when reading developed before expressive language at age 3." It's very common for word recognition skills in hyperlexia to "appear before any expressive language has developed." (Hopper, 2003)

Other early readers (i.e., the non-hyperlexic ones) generally have age-appropriate language development. Most are also analytic language processors, not gestalt language processors. That means they acquire language differently from hyperlexic readers.

7. Social/interpersonal differences

Social differences are a key feature of hyperlexia and are another way to differentiate hyperlexia from other early precocious readers.

As Grigorenko et al. (2002) noted, "the diagnosis of hyperlexia should require a co-occurrence of interpersonal difficulties." These social differences can include difficulties with social interactions, a preference for routine and difficulties with transitions, and more.

In contrast, other early readers usually develop typically when it comes to social skills so they generally don't need much support in this area.

8. Learning style

Hyperlexic children have a "unique learning style." (What is Hyperlexia? PDF) For instance, they are gestalt learners, learn best through visual or auditory stimuli, rely on scripts and echolalia, have strong pattern recognition skills, and are literal thinkers.

As a result of this learning style, hyperlexic readers often need specific support strategies, accommodations, and modifications to help them learn and grow. Things like turning on closed captions, writing things down, modeling language in a specific way, teaching language explicitly, prioritizing comprehension, etc.

Other early readers, on the other hand, will have varied learning styles. They also won't necessarily need specific supports, accommodations, or modifications at school or at home.

9. Repetitive behaviors

Repetitive behaviors are quite common in hyperlexia, but less so with other early readers. Think stimming, organizing things in alphabetical order, reading the same books repeatedly, repeating the same word or sentence over and over, scripting from media, preference for routines, or repetitive play. You will see all of these with hyperlexic readers, but not necessarily with other precocious readers.

10. Diagnostic criteria

Hyperlexia is often associated with autism so the presence of autistic features can also help us differentiate hyperlexic readers from other early readers.

In other words, precocious reading isn't necessarily linked to a specific neurodevelopmental disorder or neurodivergence. However, in contrast, "the presence of an accompanying neurodevelopmental disorder" (Ostrolenk et al., 2017) is a feature that consistently describes hyperlexia.

Now will all hyperlexic readers be autistic? No, but they will likely be identified with some other neurodivergence, language disorder, or neurodevelopmental disorder.

Remember, if a child is hyperlexic, they are neurodivergent.

Therefore, the "inclusion of precocious reading in otherwise normal children as a form of hyperlexia seems unnecessary and may detract from those children who are hyperlexic and need educational and other support." (Hopper, 2003). After all, those who would be considered hyperlexia type 1 according to Treffert's (very outdated and problematic) subtypes "do not show any sign of developmental disorder. They do not qualify as hyperlexic...and are called precocious readers in most articles." (Ostrolenk et al., 2017)

Some Final Notes on Hyperlexia vs. Precocious Readers

While it might be tempting to lump all early readers together (like so many people unfortunately do), not all early readers are the same, as you can see. Hyperlexic readers differ from other early precocious readers in a lot of ways.

Besides, it does a great disservice to those who are hyperlexic and require additional support to be lumped in with other precocious readers.

Our hyperlexic learners need strategies and supports that are tailored to their unique needs and learning style. So, it's incredibly important to distinguish them from other early readers because of these differing needs.

It's also important to remember that "hyperlexia is defined by a very specific pattern of compulsive interest and exceptional skills, and we would like to 'preserve the concept of hyperlexia' for this unique profile." (Ostrolenk et al., 2017). In order to do that, though, we need people to stop saying that hyperlexia just means early reading. Hyperlexia is so much more than that.